I love the 4th of July. I’m a sucker for family gatherings, parades, and fireworks. I confess, however, as I look forward to celebrating our Independence Day tomorrow, I’m a little worried about the state of our great nation. Correction, I look at the state of our politics today and I am depressed. Our elections cycle has shifted from once every four years to a continual campaign of rhetorical hysteria and attacks on the patriotism of anyone who holds a different view. Our 24-hour news cycle amplified logarithmically by social media has focussed almost exclusively on our differences. It seems everyone is concerned that the upcoming presidential election will once again be The most important in our Nation’s history. And it’s 17 months away!

The only prediction I can make with absolute certainty is that we’ll all be sick of it by election day.

When I find myself anxious or frustrated, I often try to shift my perspective. In this case, as we celebrate our nation’s 247th birthday, it is worth gaining a little historical perspective. It is worth thinking about E Pluribus Unum.

E Pluribus Unum. Out of many, one. It served our nation’s motto from 1782 until 1956 when we replaced it with In God We Trust. It has 13 letters, one for each of the original 13 colonies. We print it on every dollar bill. It is emblazoned across the scroll and clenched in the eagle’s beak on the Great Seal of the United States.

E Pluribus Unum is important because the Declaration of Independence was not only a claim of separation but commitment of unity. One cannot exist without the other. It sounds obvious today but it was not at the time.

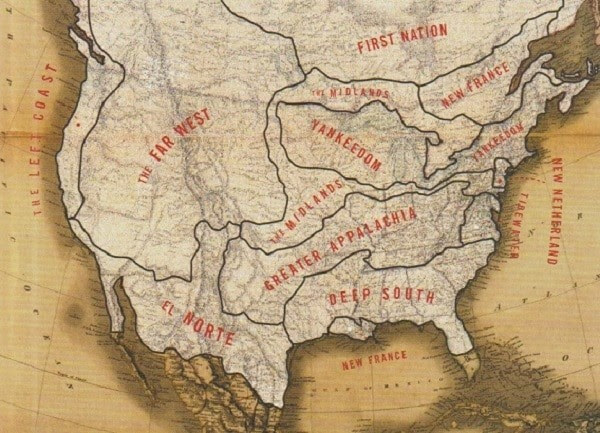

Before our nation was The* United States of America, it was 13 independent colonies. However, when I say “independent,” I don’t mean independent like our states are independent today; I mean independent, independent. As Colin Woodard points out in his absolutely amazing history American Nations, “The original North American colonies were settled by people from distinct regions of the British Island, and from France, the Netherlands, and Spain, each with their own religious, political and ethnographic characteristics.” Far from sharing a common set of cultural values and goals, they regarded each other as competitors – for land, settlers and capital. Occasionally, they were enemies as the wars of Europe spilled across the Atlantic. Writes Woodard,

“For generations these distinct cultural hearths developed into remarkable isolation from one another, consolidating characteristic values, practices, dialects, and ideals. Some championed individualism, others utopian social reform. Some believed themselves divided by divine purpose, others championed freedom of conscience and inquiry. Some embraced Anglo-Saxon Protestant identity, others ethnic and religious pluralism. Some valued equality and democratic participation, others deference to a traditional aristocratic order.”

Thus, when our forefathers met in Philadelphia for the first Continental Congress in September, 1774, they didn’t just represent separate political states, but several “Nations,” each with a distinct culture, ethnic origin, and historical experience.

- Today’s New England – Yankeedom “A culture that put great emphasis on education, local political control, and the pursuit of the ‘greater good’ of the community, even if it meant individual self-denial.”

- New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey – New Netherland. “A global commercial trading society: multi-ethnic, multi-religious, speculative, materialistic, mercantile and free traditions…[with] a profound tolerance of diversity and an unflinching commitment to freedom of inquiry.”

- Parts of New Jersey and Pennsylvania made up the Midlands. “Founded by English Quakers, who welcomed people of many nations and creeds to their utopian colonies…pluralistic and organized around the middle class. Political opinion has been moderate, even apathetic.”

Virginia and the areas surrounding it – Tidewater. “The most powerful nation during the colonial period and the Early Republic, has always been a fundamentally conservative region, with a high value placed on respect for authority and tradition and very little on equality or public participation in politics.”

Deep South: “Founded by Barbados slave lords as a West Indies-style slave society…The Bastion of white supremacy, aristocratic privilege, and a version of classical Republicanism modeled on the slave states of the ancient world, where democracy was a privilege of the few and enslavement the natural lot of many.”

Thus, when they came together, they had far less in common than you might imagine. Indeed, they also didn’t have an agenda, with the only real point of discussion being how they might respond to the actions of the British, which none of them liked. The only thing they could agree upon was to boycott British goods. But before they could meet again, the first shots of the American Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. By then, they knew that if they didn’t unite, they would never be rid of British rule.

And when the war was over and it was time to forge a new nation, they knew they had to make room for very different ideas of what a society can and should be. They were very suspicious of a strong central government and hated the idea of a standing army. Each region wanted to maintain its independence while benefiting from their collective strength. Thus, they developed a system that balanced the needs of all states, regardless of their distinct cultures, values, economies and traditions.

The result was a rebirth of republican democracy and the greatest, most powerful nation this world has ever seen.

When the Revolutionary War ended and settlement spread across the country, the “nations” persisted and were joined by others.

- To the immediate west was Greater Appalachia: “Founded in the early eighteenth century by wave upon wave of rough, bellicose settles from the war-ravaged borderlands of Northern Ireland, northern England, and the Scottish lowlands…Intensely suspicious of aristocrats and social reformers alike…Combative culture.”

- West of the Deep South was New France (New Orleans/Quebec): “Down to earth, egalitarian and consensus-driven…the most liberal people on the continent” at the time.

- To the South was El Norte – Texas: “Oldest of the Euro-American nations…A place apart, where Hispanic language, culture, and societal norms dominate…Both sides of the United States-Mexico boundary are really part of the same norteno culture.”

- The Far West – hot, dry and remote: “The colonization of much of the region was facilitated and directed by large corporations headquartered in distant [cities] or by the federal government…The region remains in a state of semi-dependency. Its political class tends to revile the federal government for interfering in its affairs…while demanding it to continue to receive federal largess.”

- The Left Coast. “A Chile-shaped nation pinned between the Pacific and the Cascade and Coast mountain ranges…Combines Yankee faith in good government and social reform with a commitment to individual self-exploration and discovery.”

Today, each region maintains its distinct identity and set of ideals and our country has prospered.

My fear is that we’ve lost the lesson of our history. We became strong not because we forged a single national identity. We are strong because we learned to build a larger nation state while allowing for distinct regional identities.

What’s changed is the way we’re fighting. We’re no longer fighting about policy but politics. We spend our days bashing whoever doesn’t agree with us. We label them “other” “liars,” and “traitors”. We demonize them as “unAmerican.” We defining ourselves less by what we stand for and more for who we stand against. Anyone who disagrees is a potential threat to our existence. Compromise is weakness. Our politics have shifted from trying to get along and build bridges between our distant views to gathering armies and trying to crush the other side. Both sides are guilty. We’re trying to impose our will on others as opposed to looking for ways that we can live, work and play alongside people who come from different American Nations.

As Abraham Lincoln acknowledged, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” Our founding fathers knew it and built an incredible system of government. It wasn’t perfect and there were enormous compromises that left women and blacks completely out of it. But it has endured for 247 years. We have endured because we allow for people to live the way they want to live. We share a defense, an economy, a language, and a belief in the American dream. We don’t necessarily have to share everything else to be successful as a nation.

So on this 4th of July, I hope you will read the Declaration of Independence and spend a little time thinking about E Pluribus Unum. We are many. We became one. We are stronger together. We don’t have to agree on everything. We never have. We may never in the future. We’ve got 247 years of shared history together and — because of our differences — have built the strongest and wealthiest nation the world has ever seen. We have stood as a beacon of hope for countless other countries for democracy. We have been, as Ronald Reagan used to say, “That shining city upon a hill.” But the beacon of hope dims as we fight among ourselves, convinced that we must convince everyone of our position, our policy, our world view or it comes apart. I don’t buy it. We are 50 states. If the people of California want to live one way, Great! Let them. If those in Georgia, Florida, New York, or New Hampshire want to live other ways? Fantastic. If we don’t like the policies or culture where we are living, we can move! But that only works if we maintain our fundamental belief in E Pluribus Unum. Out of many, one.

Happy Independence Day!

Onward!

Jeff

*When people first referred to our country, they referred to it as, “These United States.” It was not until after the Civil War that Americans referred to our country as “The United States.” The difference is more than simple language – the former is a collection of states, the latter a single national unit.